Over the last few years we’ve started to see a lot of board game adaptations of video games. It’s a trend that shows no signs of slowing down. Why are we seeing more and more of them, and most importantly – are they any good?

Having a quick look at BGG tells me there are over 20¹ board game adaptations of video games coming out in the next year or so. Go back ten years however, and you’re looking at around a quarter² of that, if you’re not counting Monopoly or Risk cash-ins (and I’m not). It’s a trend that only looks like it’s going to increase as time goes on, with video games set in concrete as the biggest entertainment industry³ in the world, and tabletop games seeing incredible growth recently, with no signs of slowing down⁴.

Filling a gap that isn’t there

The obvious and most cynical answer to the question “why do people make board games based on video games?”, is money. Video games are big business, tabletop games are worth billions, so it makes financial sense to try to use the big names and franchises in video games to boost sales of board and card games. Gamers also are often likely to enjoy both formats independently, and that’s easy money! That’s all well and good, we live in a world of rampant capitalism after all, but for me, as a board game fan, why should I be interested?

The beauty of a good video game is that it does something you can’t do in the real world. It can create worlds, stories, and experiences that cannot exist. A good game can put us in control of anything from an ant to the leader of an intergalactic empire. The worlds exist digitally, and we can be immersed in them. Board games offer an abstraction of these things. They give us puzzles, adventures, and mechanisms to explore, sure, but there’s a lot of investment from the players to create immersion in the theme, and in the worlds created.

Yet, despite the fact we already know that a tabletop game cannot give us this same level of immersion or experience as its digital counterpart, we throw our money at them regardless. Why? Familiarity is one of the main reasons. We love the original game and want a reminder of that, and a way of expressing that affection. Let’s have a look at some examples of what makes a board game version of a video game work, and where they can fall short.

The natural fit games

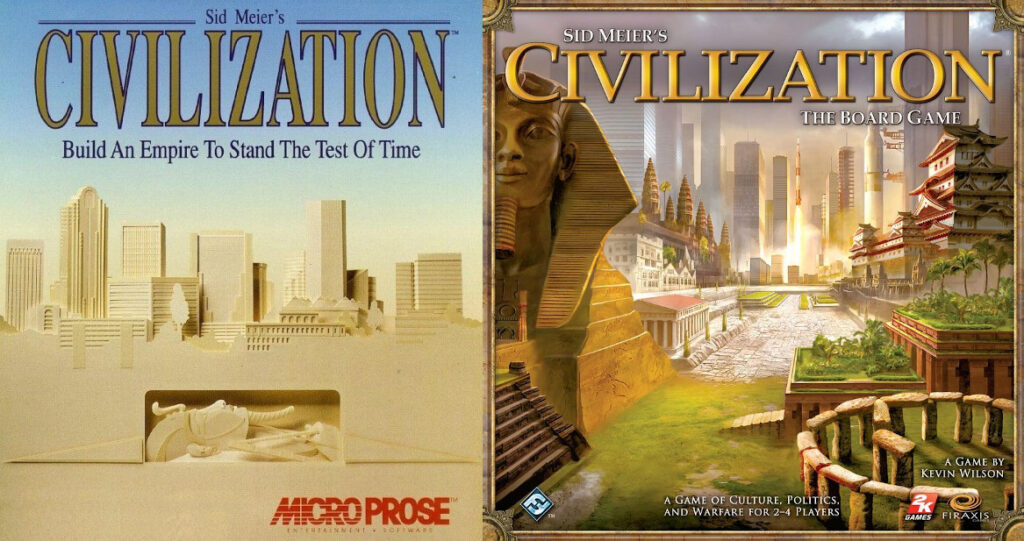

Turn-based strategy is the most natural fit when you’re looking at a genre of video game to try to translate to the dining room table. When you look at the likes of Civilization, you can see why. In both versions players are taking turns to build cities, to move units around the map, and to try to conquer the world. Sid Meier & Bruce Shelley (designers of the video game) and Francis Tresham (designer of the original Civilization board game) have tangled roots in the past anyway, but that’s a post for another day.

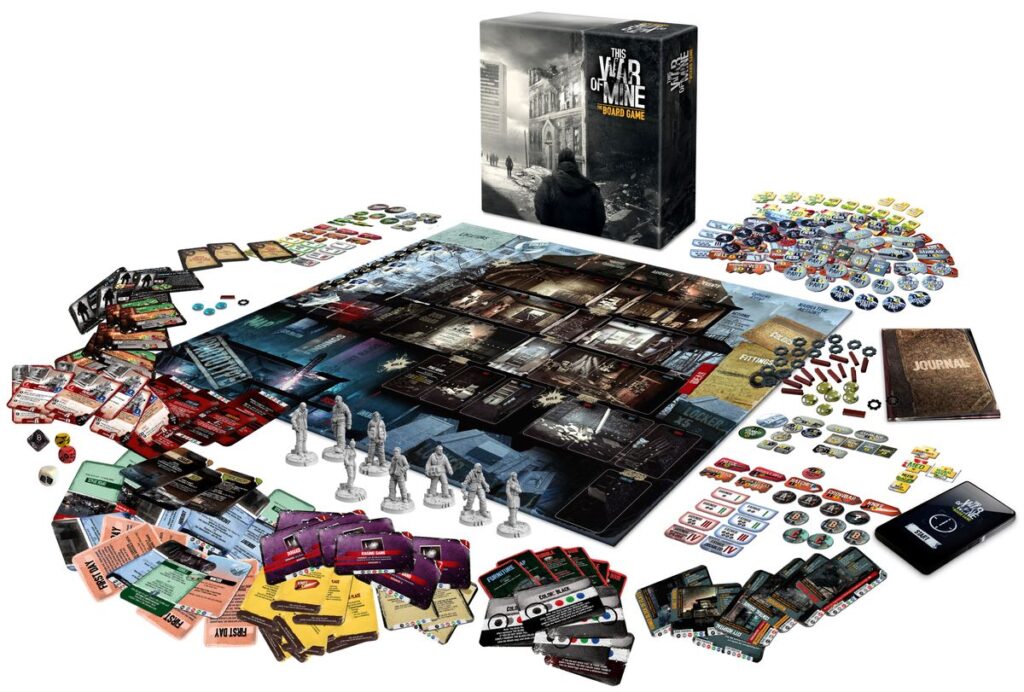

Then you get games like Awaken Realms’ adaptation of This War of Mine, which took a critically acclaimed video game and turned it into a game which as well as being excellent, also reached people with its message and theme. This review of the game, written by a survivor of the siege of Sarajevo, deserves your attention. The game adapted the strategy of its digital predecessor and was a hit, but it’s that word – ‘adapted’ – which is key.

Many of the other good tabletop adaptations are in the same vein: Age of Empires III, Starcraft, X-Com, Master of Orion, Cities Skylines. They’re a perfect natural fit and you can see them capturing the same feel as the video game they’re each based on, because there was already a feeling of scale and distance in the game they’re drawing from. By marrying good presentation and keeping the same base feeling of strategy – albeit handled differently – designers can encapsulate the familiarity that fans of the originals are looking for.

For example, Starcraft is a notoriously fast action video game, and the board game managed to capture the battle feel of swarms of opposing units, with cards. Then we’ve got Master of Orion, a grand scale, turn-based, space 4X video game, which became an engine-building board game. Smart decisions get made in adapting games like Superhot, which translates effortlessly from a time-based shooter into a card-aligning puzzle game, and makes you see the mechanism from the videogame in a new light.

It doesn’t always go so well though. In early 2021 a board game adaptation of Stardew Valley was announced and released, coming as a complete shock to everyone. There was no fanfare, no crowdfunding, no previews, just – “here you go, a new game”. I’ve not played it, as it’s only had a US release so far, but I’ve watched and read a lot of reviews, and two things stand out. Firstly, the theme and feel is there from the video game. It looks like Stardew Valley, and it captures the aesthetic of the much-loved game. The gameplay, however, appears to have far too much luck involved. I like a little bit of luck in a game, but it needs to be balanced. In Stardew Valley, luck is so baked-in that winning can become all-but-impossible with plenty of the game left to play. A quick look at the variants forum for the game on BGG shows the effort people are going to to fix the game already, so beloved is the franchise.

The “What? How? Why?” games

Then we have the games which really leave me wondering how they came into being. Dark Souls, Doom, Bloodborne, Gears of War, Horizon: Zero Dawn. Heavy action games that spawned turn-based tabletop games. Now, to be fair to at least a couple of those, they’re pretty decent games, but Dark Souls is the game I’ll use as an example here.

From Software’s Dark Souls is notoriously hard. It’s one of the things that people really appreciated about the video game, that you had to work at it to play well. The board game captures this feeling of difficulty – You’ll die. You’ll die a lot. Unfortunately, that’s where most of the similarities end. l asked a big Facebook board game group for their opinions on these games, and they mostly mirrored this, noting that what made the video game feel special is the way it rewarded careful exploration, and learning patterns, and that the board game is missing that experience.

This is the difficulty with making the transition from a screen to a table. Trying to capture what made a game feel special is very hard to do when that ‘special’ revolves around the movement, the ambience, and the world-building – especially in a first- or third-person game. Horizon: Zero Dawn’s board game had similar shortcomings, and although it has its fans, it was quickly forgotten and seldom recommended. The game is dragged-out and the variety of enemies and feeling of exploration – both key features of the video game – are absent.

Doing it well

The reason Doom and Gears of War did so well is because they don’t try to recreate the experience of the video game. Doom, for instance, was turned into what is basically a dungeon crawler. It’s ironic that capturing the frantic experience of a first-person shooter has best been done so far by games which don’t have a license but aim squarely at that goal – Adrenaline being the best-reviewed example.

Meanwhile Gears of War combined dice and cards in a clever way to build a sense of foreboding and tension, which was one of the key features of the video game: being up against it. Both did well because they drew on themes from the video games, but completely rewrote the styles of the games.

Another good example is the Kingdom Rush series. A tower defence game doesn’t initially sound like it’d find itself at home on a table, but when you boil it down to its essence, you can see why it works. Tower defence games, at their core, are a game of numbers. Enemies with a combined strength of X are going to move across the map in T units of time, and your towers deal Y damage per second. As long as you can deal enough damage in that timeframe, you’ll succeed. These are formulas you can recreate in a physical format. Kingdom Rush and the follow up, Rift in Time, are both great examples of an unexpected title which translates well to a physical game.

Games on the horizon

Things look as though they may be improving in the digital-to-physical realm in the near future. I’ve paid a lot of attention to Frostpunk, as I love the video game. From what I’ve watched and read about it, it sounds as though they’ve maintained that tense feeling of trying to survive the harsh weather, and force you to make difficult decisions about the plight of your people. Prison Architect seems to have made the right concessions about what it can and can’t do to ape its digital counterpart, and has one of my favourite designers (Dávid Turczi) heavily involved. After speaking to the project manager for the game, I have high hopes for it.

Even with these natural fit games though, people are still inclined to just throw money at a franchise just because of the name. Stellaris is a great space 4X video game which recently kickstarted a board game version. A space 4X is something board games do brilliantly – just look at Twilight Imperium or Eclipse – so you’d think Stellaris is an obvious choice. When the Kickstarter began it absolutely destroyed its goal in a few hours. They originally aimed for $50,000 and ended up raising just over 2.5 million. However, the majority of those pledges were made when there was no gameplay explanation, no videos, no rulebook to read through. There was just an explanation of the sort of game it intends to be, and a lot of renders of minis and cards.

Let that sink in. Without knowing the first thing about how a game will actually play, people pledged millions of dollars to a game based on its name, with its publisher (Academy Games) being relatively unknown unless you’re into wargames. That’s the power that these much-loved franchises have, and that’s where the danger lies. Get the right studio and designers behind an adaptation, and you can have something really special. If it goes the other way though, you can end up with a game which is wearing the right clothing, but swings and misses as an experience.

With a popular franchise’s name in their hands, publishers wield a huge amount of influence. My hope is that we see a continued drive to bring the feel of our favourite video games to the table, even if that means taking them in unexpected directions.

Special thanks to Dr Douglas Brown for his input and expertise.

¹ BGG link

² BGG link

³ Statista – entertainment industry value

⁴ Board games market outlook & forecast