I’m going to say right at the outset that I know 1970s American politics isn’t a theme that’s going to set everyone’s heart a-flutter. However, I’d urge you to read this review all the same, because to turn your nose up at Watergate without looking deeper could be doing your collection a major disservice.

Watergate – Some Background

It’s important to give a little bit of background here, because the theme is so deeply ingrained in the game. Watergate, better known as the Watergate Scandal, was a scandal between 1972 and 1974 in the US. At its heart the Nixon administration paid five people to break into the headquarters of the Democratic National Committee, and then continuously tried to cover up its involvement. Two reporters from The Washington Post (Woodward and Bernstein), among others, uncovered evidence of the involvement, and eventually Nixon was forced to resign, and nearly 50 members of his administration were convicted.

It was an enormous national scandal and the media vs politics ruckus that ensued is still the subject of films and books to this day.

Now you’ve had the (very) short version, let’s have a look at the game.

What’s In The Box?

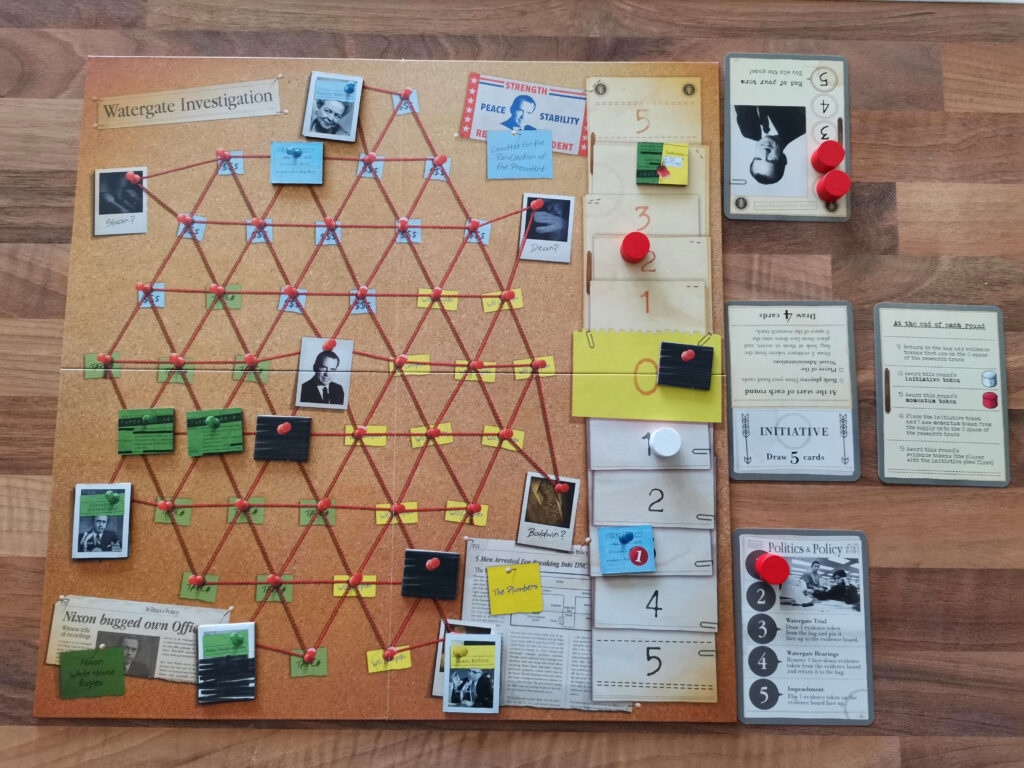

Watergate comes in a small box, and in that box is a small board, two decks of cards, a bag full of small evidence tokens and some wooden markers. That’s all there is, and that’s all it needs really. It’s a game for two players only, and happily sits on a small table between the players, which is the way it’s designed to be played.

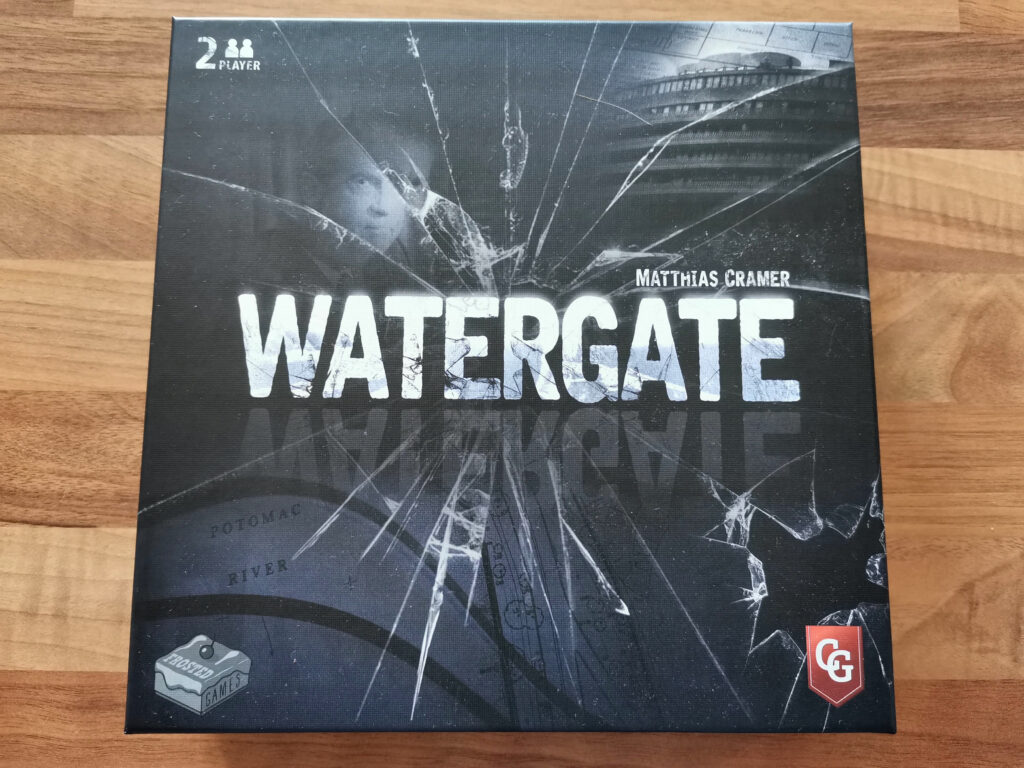

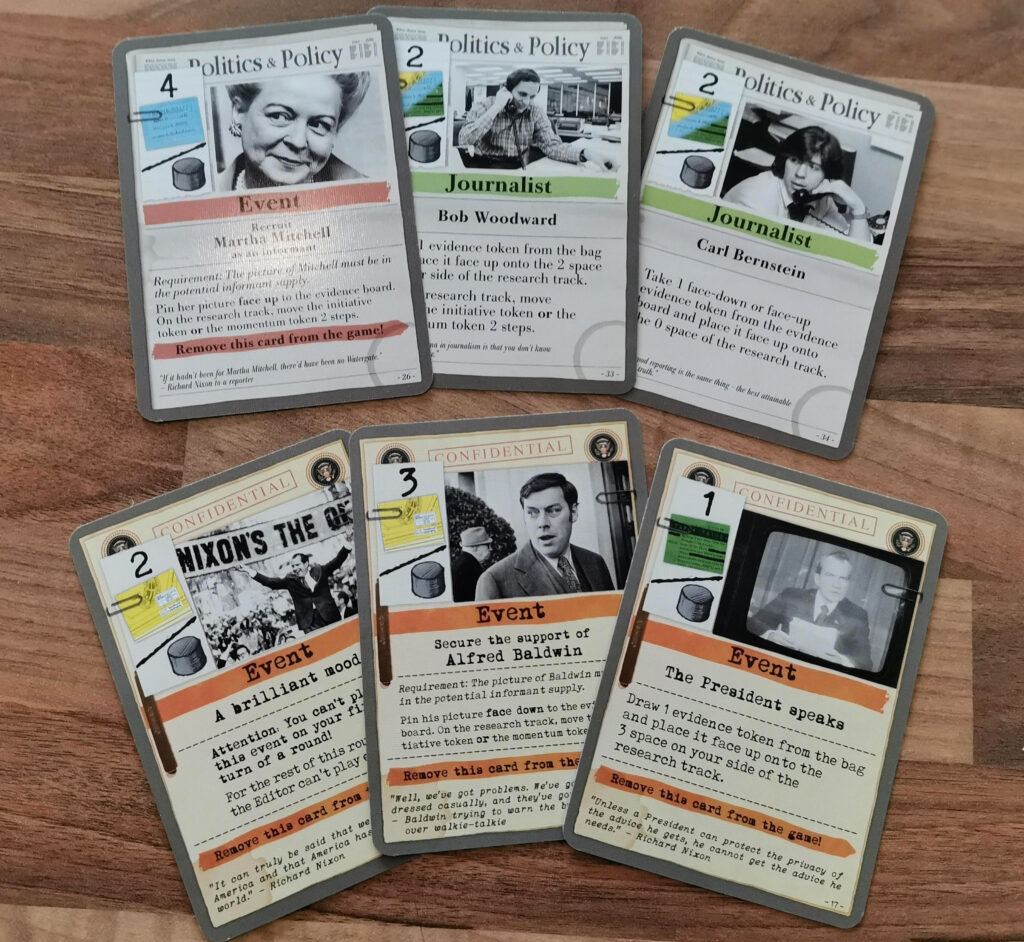

The board is nice and sturdy, with really nice artwork and graphic design. I love the cards, they have a lovely soft finish and are slightly larger than standard playing card size. In Watergate the cards are the game really, so I’m happy so much attention to detail is paid. The photographs of the real people are included on each card, along with clear iconography, and some really nice flavour/history text on each one.

It’s nice to have a black cloth bag included too, for blind drawing of the evidence tokens. The publisher could have taken the cheaper option that many do, and told you to place them all face-down on the table, but they didn’t.

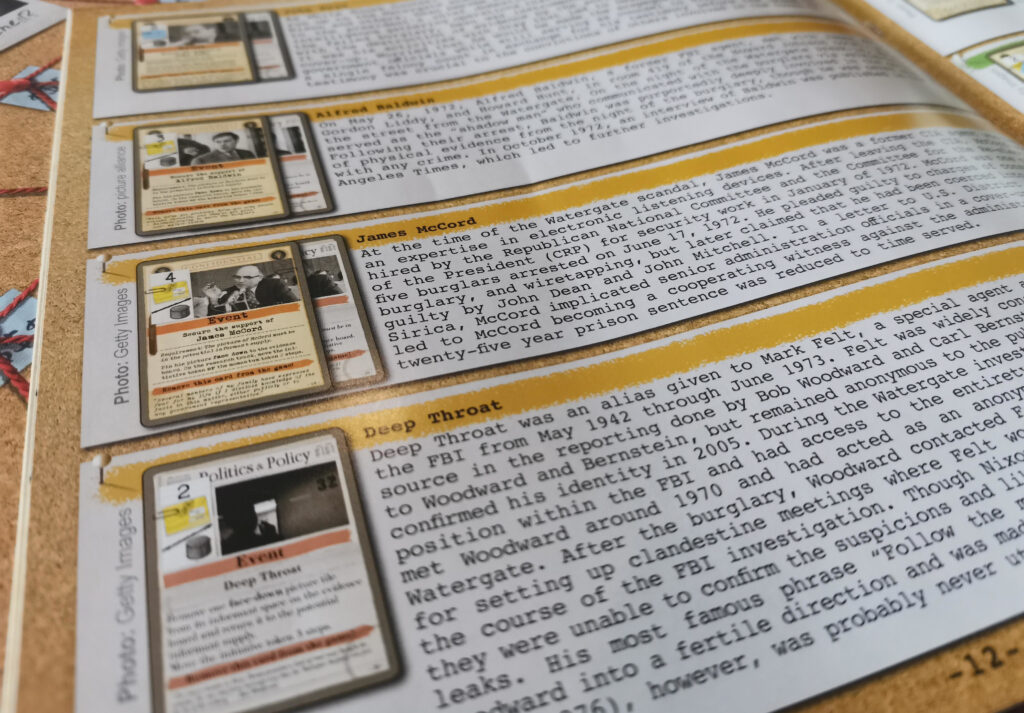

The rule book deserves a special mention. Not only does it have really clear instructions and setup diagrams, with examples of every rule, but it has bios of everyone involved in the game, and a well-researched history of events.

You could easily take this with you anywhere, and I could see it being a great one to take to the pub for a few drinks with a friend.

How Does It Play?

Before I played it, I’d heard Watergate described as ‘Twilight Struggle Lite’. Twilight Struggle, if you don’t know, is one of the best two-player games ever made, which has a tug of war of power through playing cards. It’s also very deep and needs a lot of concentration. So when I heard that comparison, I was a little worried, as I’ve played Twilight Struggle, and it is brilliant, but it’s hard to learn and doesn’t easily win over new players.

Now that I’ve played it, I can happily say that while I can see why it got that comparison, it’s nowhere near as dense, and that’s a good thing.

Setup

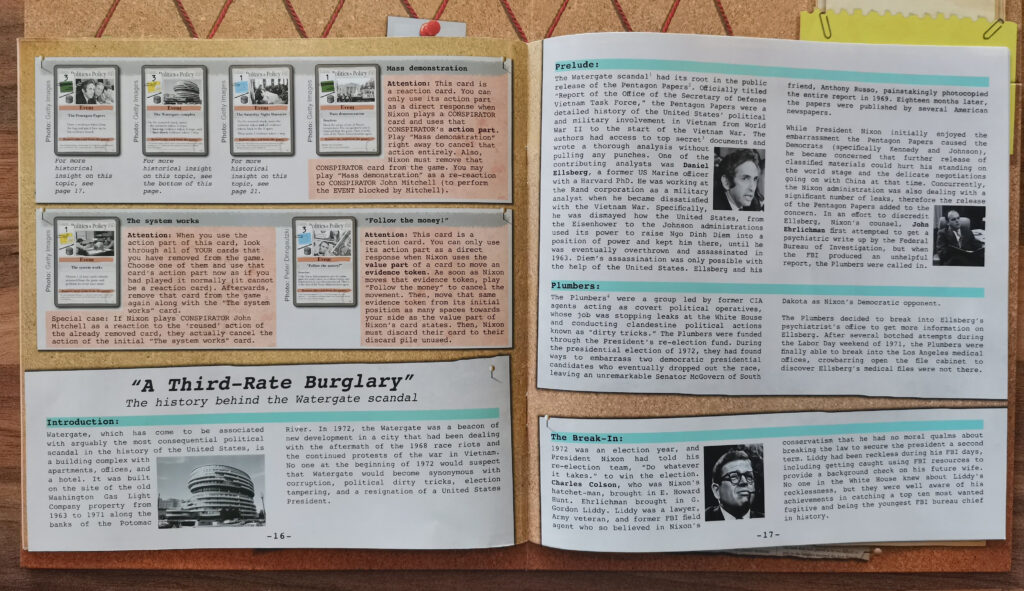

The board is placed between the two players, with the player taking the role of the newspaper editor having the board facing them, and the Nixon administration (referred to as Nixon) viewing it upside-down. Each player has a deck of cards unique to their side, and these cards are what drive the game.

The board itself features a cork pin board design for most of it, with a web of strings and pins on it, much like you’d expect to see in a film when they uncover someone’s secret research into a subject. Strings linking people. places and things – that sort of thing. On the right-hand side of the board is a research track, with a zero space in the middle, and five steps on each players’ side. To the side of the board is an Initiative card which always points an arrow to one player or the other. Whoever it points at draws five cards each round, and plays first, and the other draws four cards instead.

The bag of evidence tokens and seven tiles representing potential informants or supporters sit on the table next to the board. Setup takes five minutes at most, which means you can get into playing really quickly, unlike something which needs a lot or preparation like Paladins of the West Kingdom.

Playing The Game

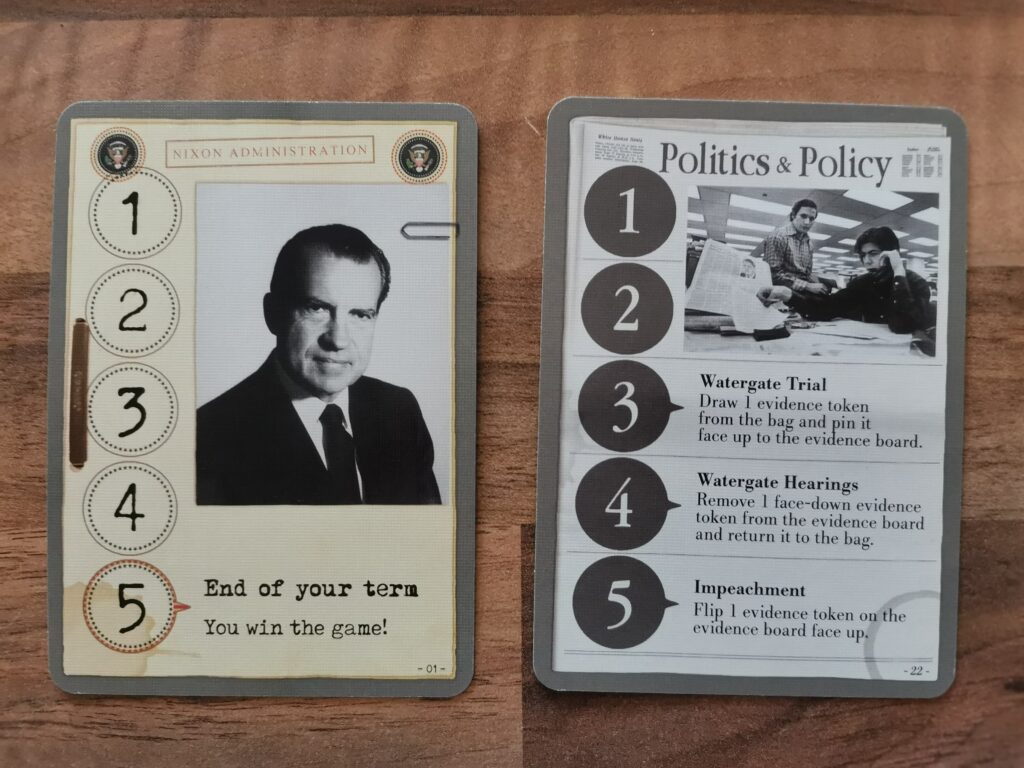

Watergate is an asymmetric game. Nixon has to gain five momentum tokens to win, while the editor has to link any two informants to Nixon on the board, by placing connected evidence tokens on it. On your turn you play a card from your hand, and each card has two parts. The top part of the card lets you move any evidence token of a matching colour towards you by the number of steps written on the card, or you can choose to move either the round’s momentum token, or the initiative token towards you instead.

The bottom of the card has more specific options, and these are usually Events. Each event marks a change in the game and usually that card is then removed from the game, instead of going onto your discard pile. These events can see informants being added to the board, tokens being drawn blind from the bag and placed on the board, or even preventing the other player from playing their own events in that round. The payoff for losing a card permanently can be huge, but has to be balanced with losing whatever power that card had for moving tokens instead, so it’s a really nice balancing act.

Players play their cards one after another, and this is where the beauty of the game comes to the fore. It’s this magnificent tug of war, where the three evidence tokens, the initiative marker, and the momentum token are constantly pulled between each player’s sides of the board. If you manage to get any item to the fifth and final space on your side of the research track, you instantly claim it. The round ends when both players have no cards left, and whichever tokens are on your side of the board, you get to keep.

This all sounds pretty straightforward, and even writing this now it sounds simple even to me, so let me give you an example of the sorts of things running through your mind for every card of every round of the game.

Difficult Decisions

Let’s put ourselves in the role of the editor, and let’s say we’re a couple of rounds into the game. Nixon has grabbed two of the five momentum tokens he needs, and we’ve managed to add one of the blue informants to the board. Our goal, as editor, is to link our informants – on the outside of the web – to Nixon, in the centre. We can see there’s a blue evidence token on the research track this round, which would go a long way towards making that link.

The thing is though, we can see the momentum token is already two steps towards Nixon. If the round ends and it’s still there, he gets it and is another step closer to victory. So should we focus using our actions to drag that little red token back to our side of the board, to scupper him? Or should we concentrate on moving that blue token towards us? Or maybe we should pull the initiative token towards us more. That has the benefit of giving us more cards in the next round, and whoever wins it at the end of a round gets to place their evidence tokens on the web first.

At the same time as we’re running over all these options, Nixon is doing the same thing. That momentum token would be really good for him, but in the same breath, if he were to take that blue evidence token, he could flip it to its black side and place it, blocking links for the editor.

On top of all of that, every card has it’s special actions and events, and the entire time neither of you knows what the other is holding, or the order they’re going to play them in. Tense stuff. So much of this game is about reading your opponent. In your first games you’re paying attention to the mechanics of playing, but you soon find yourself watching the other player’s eyes and trying to read the subconscious exposure of their plans.

“Is she looking at that evidence token? She is! She keeps looking at that space on the top of the evidence board, she wants to block me I bet…“

As soon as either player accomplishes their goal the game ends immediately, and the loser starts setting it up for another game, demanding instant revenge. That’s not in the rule book, it’s just what happens.

Final Thoughts

That’s all there is to Watergate. It’s not a very complicated game, but goodness, it’s a deep one. I love the constant ebb and flow, watching the pieces pulled back and forth on the track like a ageing armchair in a messy divorce. You might not desperately want or need it, but you’ll be damned if the other person’s getting it! Just as you think you’ve worked out a strategy for the current round, it’s almost guaranteed the other player will do something that ruins your perfect plans.

The theme is so thick and heavy in this game, that I’d really recommend immersing yourself in it, just to add to the overall atmosphere. This is a site about games, not films, but I highly recommend watching All The President’s Men (Dustin Hoffman and Robert Redford) if you haven’t seen it (or even if you have). If that doesn’t get you itching to play this, nothing will.

I can see the comparison to Twilight Struggle, but it’s not a good one in my opinion. Twilight Struggle’s cards see each player playing events beneficial to their opponent in their own turns, whereas the cards in Watergate really only benefit yourself, so there’s seldom the choice of “What’s the least worst option here?”, which is what Twilight Struggle excels at. There isn’t too much to keep track of in this game. Both of you can see the evidence board, and know the state of play. Both of you know who has the most cards, and both of you can see who’s going to win what at the end of the round. The only secret is what colour the evidence tokens are each round, as Nixon draws them and looks at the colours. The substance of the game comes in choosing what to do with that information.

I wasn’t really aware of Matthias Cramer before Watergate (although now I realise he’s also the designer of the Glen More games), but he’s come up with something really special here. It’s simple enough in its mechanics to teach to almost anyone, very quickly, but it will take a long time to get really good at. What I absolutely love about this game is how after just a couple of plays, those mechanics disappear. That’s something which in my experience only happens with great two-player games, they become a vessel, a method for one person to compete with the other on a level playing field. The game, as such, is each player trying to outsmart the other, and it’s brilliant.

I highly recommend Watergate for anyone that has a regular ‘player two’. Its clever play, quick setup and portability make it an instant modern classic in my opinion.