Viscounts, the third and final installment in Garphill Games’ West Kingdom trilogy is here, picking up the baton from Paladins, and running in a different direction. Rondels and deck-building in the same game? Be still my beating heart!

Designer: Shem Phillips, S J MacDonald

Publisher: Garphill Games / Renegade Game Studios

Art: Mihajlo Dimitrievski

Players: 1-4

Playing time: 60-90 minutes

Introduction

First we had Architects, which was a bit like a grown-up Stone Age worker placement game. A good game, but not too heavy. Then came Paladins, which really upped the ante and got a lot heavier, and did a really nice twist on the standard worker placement formula. Towards the end of 2020, Viscounts arrived, and one was of a growing trend of combining deck-building and other mechanics.

In this game we’re sending our viscounts around the kingdom, constructing buildings, transcribing manuscripts, and increasing our nobles’ influence in the castle. To do that we’re using our band of townsfolk and criminals, gaining deeds and converting debts, trying to prove ourselves the most powerful.

What’s In The Box?

Shem Phillips’ games come in these neat, square boxes. They don’t take up much space, but getting all the pieces in there is a task in itself sometimes (cough.. Paladins). There’s plenty in the Viscounts box too.

The board is made up of five sections, each of which are double-sided, The side you use depends on the number of players. You place them down in random order, then the plastic castle – randomly oriented – locks the boards in place with an extremely satisfying click. Then there are piles of cardboard manuscripts placed around the board, and piles of townsfolk cards.

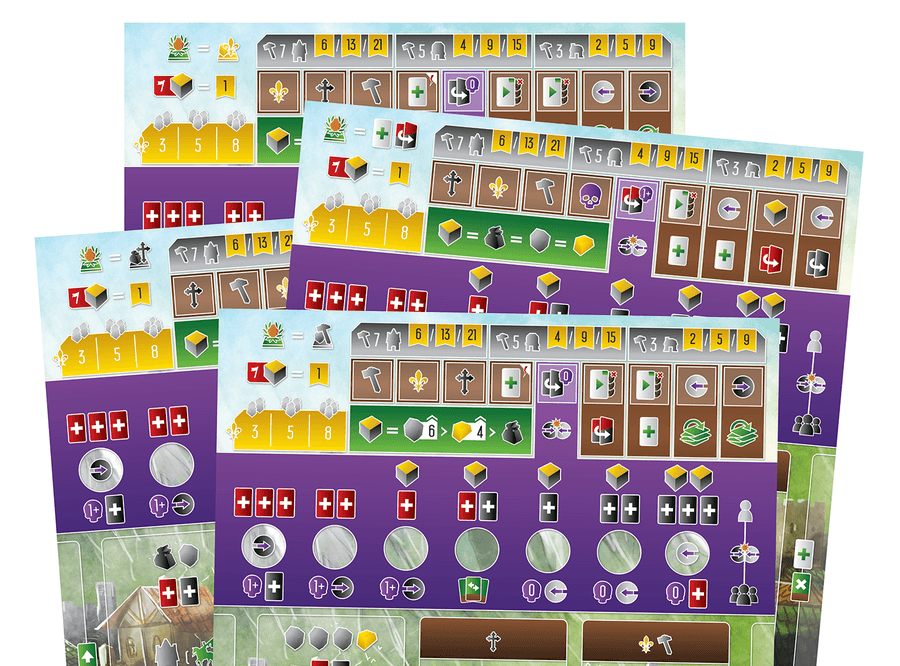

Resources in Viscounts are represented with wooden inkwells, gold and stone, along with the now de-facto cardboard coins (or metal if you’re lucky enough to have upgraded them). The player boards are thin card, much like the ones from Terraforming Mars. They’re the only thing which feels cheap in the game, but I understand why they’re so thin. I’m not sure everything would have fit in the box if they were thick cardstock.

Cards On The Table

As you might expect in a game with deck-building, there are quite a lot of cards included in Viscounts. There’s a starting deck of cards for each player, which are identical, and then a deck of townsfolk who can later be added to players’ decks. Finally, for the full-size cards there’s a deck of AI cards for the solo mode.

There’s also a whole bunch of the smaller size cards that feature in the other games. There’s a stack each of debts and deeds, which play an important role in the game, and some other cards for marking bonuses for actions later in the game.

The quality of all of the components, as you’d expect by now, is really high. The only negative is as I mentioned above, the player boards are more like player mats. Shiny card. But the big difference between this game and something like Terraforming Mars, is that the main things you’ll place on this board are cards, so a small bump or two won’t matter even if things do move.

How Does It Play?

So, we’ve got our boards placed in a random order, and the castle’s clicked into the middle. Each player has their starting deck, their board, and they added a combination of starting resources and Hero card, which gets shuffled into their deck. The viscount markers go to their designated spots on the board, and we can start.

Action Stations

As you might expect from a euro game, the core of Viscounts revolves around taking actions. At the most basic level, a turn consists of playing a card onto your board (more on this later), moving your viscount the requisite number of spaces printed on that card, and then taking an action.

There are three main ways to score points in Viscounts, and each of these has an associated action. Constructing a Building lets you take a spend hammers and stone, take a building from your player board, and occupy a space around the outer ring of the board. As you might expect, there are bonuses from doing this. The spot you build on gives you something, if you build next to another building and there’s a line between them, both building owners get whatever’s on that line, and the space on your board where that building used to live, now gives you something extra. Nice.

While you’re on that outer ring, you could be trading instead, Trading sees you cashing in your silver and any money bag icons on your board in exchange for resources, or flipping deed or debt cards. This is an important action that we’ll touch on later.

If you follow paths to the inner circle of the board, there are a couple more actions to take. You could Place Workers, where spending a combination of gold and fleur de lis symbols let you add your workers to the lowest tier of the castle. This section is great fun, as when you manage to get three of your workers in one section, one moves to the space to the left, one to the right, and the third goes up a tier, giving you a bonus action or resource. Where this gets interesting though, is that if any of those workers you moved is now the third of yours in a section, the same thing happens again! And again! You get this deeply satisfying cascade of movement and bonuses from the centrepiece of the board.

Finally you could spend crosses and inkwells to transcribe manuscripts, taking the tokens from the board, gaining the bonuses on them, and setting up some set collection for end of game scoring. Any purple criminal icons are wild, and count towards any action.

Decked-Out

Even on its own, that sounds like a satisfying game in its own right. But we haven’t even looked at the player boards yet, or those cards in our hands. On your turn, you slide any cards on your board a space to the right, eventually dropping off to form a discard pile. You choose one from your hand of three cards, and play it into the now-empty space. Some cards have an immediate effect, giving you something when you play it. Some have a dropping-off effect, triggered when they fall off the end of the board, and others have an ongoing effect for the time they’re in play.

Each of these cards has one or more symbols on them, which relate to the actions from the section above. To take an action, you total up the matching symbols and the resources you have that you want to spend. So for example, to build a building you’re combining hammer icons and stones. The more of each thing you have, the more potent the version of the action you can take.

I did mention right at the top, waaaay back up there, that this game has deck-building, so what did I mean? At the end of a turn, you can buy the card next to your viscount for the cost printed on it, and add it to your discard pile. In the tradition of most deck-builders (Though not Aeon’s End), the discard pile is eventually shuffled and recycled into your draw pile. There are other actions which let you destroy cards from your deck, removing them from the game. By combining these things it’s possible to build a deck that’s very strong at one thing, by adding more of those type of symbols, and weaker in others, by weeding them out of your deck.

“He has all the virtues I dislike and none of the vices I admire.”

The last thing to mention are the two sets of polar opposites employed in the game: deeds & debts, and virtue & corruption.

Deed and debt cards are acquired throughout the game, Deeds give you 1 VP, or three when flipped, and debts are worth -2 VPs, which are cancelled if flipped and give you a free resource. It’s collecting these cards that triggers the end of the game too. Partway down each of the decks (deeds and debts) there’s a larger card, which, when revealed, signals the last turn of the game. In a fun twist though, revealing the card in the deeds debt rewards the player with the most flipped debts, and vice-versa. This means there’s a see-saw of players making sure they have enough of the deck that looks like it’s going to get triggered, which in turn moves that deck closer to being the one which triggers the end. The tension!

Finally, on each player’s board there’s a track representing virtue and corruption. A black marker starts on one end, a white one on the other. Certain actions cause the markers for one or the other to move towards each other, and when they collide there’s a resolution phase. This sees the player take a number of deeds or debts, before resetting and starting the track again. At first it doesn’t seem that important, but when you consider that pushing that track all the way to one end gives you three deeds or debts, it becomes really important to keep an eye on.

All of this pushing and shoving carries on until the end of the game is triggered, then players total up the points from what they’ve accomplished, plus any bonuses. Then to the victor, the spoils! If you don’t have any spoils, maybe replace it with a cup of tea and a chocolate hobnob.

Final Thoughts

Viscounts of the West Kingdom is a great game. I could probably just leave it there and you’d know all you need to, but you’re out of luck, because I want to tell you why I like it so much,

King Of The Castle

I have no shame in saying that one of my favourite things in this deep, strategic game, is moving all the little dudes around on the castle. It’s ridiculously satisfying. Lots of games have actions that combo up and give you stuff, but none do it in such a fun, toy-like way. I take an inordinate amount of pleasure from moving the pieces around and telling everyone else – in explicit detail – what I’m doing.

“So i add my guys here, then this one goes here, that one goes there, and this one goes up a level and gets me a free move on the first tier. I move him, there, and trigger another one. This guy goes up, flips a debt for me (thank you very much), now there’s three in there, so up he goes again to the top, and now I take a resource, and the castle lead card. Oh, and look down here, there’s four in this section now, and two of them are yours? Oh dear, off you get then. My castle! Adam’s castle!“

Yeah, I can be pretty annoying to play games with.

That’s just one part of the puzzle though. Getting the buildings off your board gives you some really powerful bonuses, like permanent bonus icons for your preferred action, and clearing a full set of buildings is worth loads of points. Collecting manuscripts is the real sleeper strategy though, the initial bonuses on them aren’t always extravagant, but the bonuses for collecting sets of different coloured ones, and the bonus cards for being first to collect three of a kind, they can lead to some crazy end-of-game scoring.

Getting The Full Picture

One thing I found in my first few plays, is that it’s very easy to get drawn into this mindset of ‘see what cards I have, see what I can do, do that, repeat’. Playing this way however, you’re not really taking advantage of the gimmick (and I really don’t like that term) of having deck-building. Choosing which cards to destroy when you can, and which you recruit into your deck, is one of those things which shows its importance more with each play.

There are usually small margins in victory in Viscounts, and a carefully crafted deck means you can do your preferred action maybe even just one more time than your opponent, and that can be the difference between winning and losing. Destroying cards not only refines your deck, but you also get the value of the card back in silver, which is also vital for certain things. You will undoubtedly reach a point in one of your games where the thing you need to complete your master plan is one… space… further… than you can move, and that single silver piece can be spent to increase your range by one.

That’s the sort of margins we’re talking about here.

Set Your Own Pace

It’s no secret that I love heavy euro games. One thing that I’ve noticed in a lot of the games I played last year is that you can always see the end of the game. In Merv you get twelve turns. In Praga Caput Regni it’s something like 16. Even in Shem’s own Paladins of the West Kingdom, there are eight rounds, then it’s done. Don’t get me wrong, I don’t mind that at all, all of those games are fantastic. What it leads to though is a lot of over-analysis for the last turn, trying to squeeze the maximum points from it.

In Viscounts, the end is driven by the deed and debt decks, and when one runs out. It’s maybe a subtle difference, but an important one to me. It’s something normally in older or more light- or middle-weight games, like Stone Age, Dominion, or even Ticket To Ride. Seeing it again in Viscounts made me really appreciate the tension and meta game it brings, keeping an eye on your opponents, the cards remaining, where the virtue and corruptions are, trying to figure out if it’s worth triggering the end and watching people scramble for the last points.

Any Pieces Missing?

The danger when combining mechanics in a game is whether all the pieces of the puzzle fit together. Nobody wants a jigsaw with a piece missing, or the wrong shaped holes and nobbles? tongues? Whatever the sticky-outy bits on a jigsaw piece are called. Anyway, I digress. Viscounts marries everything together really nicely.

There is so much randomness in setup that no two games will feel the same, and there are a lot of different ways to play, and no dominant strategy. You’ll see people say that filling the castle is an easy road to win every time, but when you compare the points available for completing all the castle actions, buildings, and the maximum realistic amount of manuscripts, it really isn’t.

The deck-building is really clever. Balancing who is in your deck, who you recruit or dismiss during you turn, the order you move them across your board, and combining the icons and effects on them, it’s really nicely done. Much like moving and taking actions, the card management feels like a game in its own right, but the really important thing here is that although each part feels like a game, the way they combine is nigh-on perfect.

Deck-building, area control, resource management, player board upgrading – it’s all there, and it all works.

“Dancing With Myself, Oh Oh, Dancing With Myself”

Even Billy Idol had to entertain himself sometimes, so it’s a good job there’s a full solo mode in the box. Shem puts proper opponents in his solo games, which I really like in a solo game, and Viscounts is another excellent example of how to do it well. Paladins’ opponent was great, with variable difficulty, and Viscounts goes even further. The reverse side of each of the player mats has a different AI to play against, each focusing on a different favoured action. It’s really well done, really easy on the housekeeping, and thanks to the clear iconography and excellent player aids is really easy to do.

Solo doesn’t feel like a “I’ll have to make do with this instead of real people” option, it’s really enjoyable experience deserving to be played even if you have a regular group around you.

The TL;DR Bit

In summary Viscounts is awesome. It plays smooth, it’s great fun, it’s on the heavy side. The deck-building works, the components are great, the solo is fantastic. You can play differently every time you play, which keeps things fresh. You’ll know how to play it within your first game, and the teach is pretty painless too. If you like Garphill Games‘ other West Kingdom games, I think you’ll love this. The Mico’s distinctive art style might not be for everyone, but it’s the signature on these games, and personally I love it.

It’s cheaper than most of the games being released now, and it deserves a space in any euro fan’s collection. Is it better than Paladins? ….hmmm, ask me this time next year.